2 metrics I stopped using

The fallacies of the Shiller PE ratio and Stock Market/GDP ratio

“We are in a bubble”, “It’s the new Dotcom crash”, “The Market is clearly overvalued”: how many times do you hear these expressions?

In today’s post, we’ll illustrate the limitations of 2 financial metrics that are commonly used to measure how expensive or cheap the stock market might be.

The goal here is neither to say that these metrics are incorrect, nor to come to specific conclusions regarding the current valuation of the stock market. The idea is only to inform you about potential fallacies of these metrics.

Let’s go!

Metric #1: Shiller PE ratio

What’s the Shiller PE ratio? Here’s the formula:

Also called Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings Ratio (CAPE), is standing at 33.53 the time I’m writing. It’s simply calculated as follows:

S&P 500 Price: $4,981.80

Inflation-adjusted EPS (past 10-year average): $148.55

Shiller PE Ratio: 33.53

Apparently, values above 25 might warn of a potential stock market overvaluation, as you can see from the chart below:

What are the limitations?

This metric is heavily backward-looking. It only considers past profits and does not include any forward-looking estimate.

Investors should take into account the role of ETFs over time. Asset Under Management linked to ETFs surged from less than a trillion Market Cap of 2004 to nearly 8 Trillions in 2021. In short: there’s a much larger amount of capital investing in stocks than before.

At current interest rates, looking at Operating Margins instead of bottom-line profits would slightly make more sense to me.

Metric #2: Warren Buffett Stock Market/GDP Ratio

Even more popular than the first one, the Stock Market to GDP Ratio is calculated as follows:

It’s based on the idea that the economy and stock market valuation should more or less run in parallel over long periods of time. Values above 100% would mean the stock market is overvalued, and vice versa.

Where are we now? Apparently, pretty high, as we swing between 150% and 180%:

What are the limitations?

In general, the same limitations of the Shiller PE Ratio apply here, with a couple more notes I’d want to mention:

If we take the US GDP only, we don’t take into account the fact that 43% of the S&P 500 index is made outside the US.

The largest 7 companies in the index (the ‘Magnificent 7’) account for about 30% of the total index market capitalization, creating a distortion effect toward their current valuations.

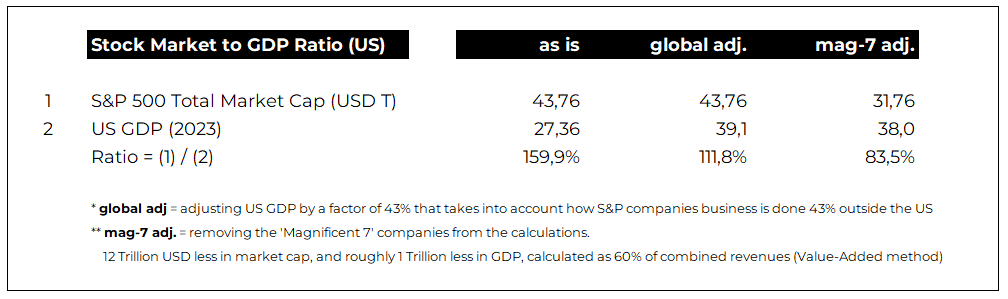

In the following exercise, we tried to neutralize both issues:

How to read this? I’ll cut to the chase:

As is = the ratio hits 160%

Adjusting for international business, the ratio decreases to 112% (I multiplied US GDP for a factor of 1.43 to reflect how 43% of S&P 500 companies’ business is run outside the US)

Removing the ‘Magnificent 7’ stocks the ratio plummets to 83.5%. I subtracted their combined market capitalization from the index and removed 60% of their revenues from the GDP (assuming they have a combined 60% Gross Margin), using a “value-added” approach to how GDP is calculated.

Again, this is not to conclude that the stock market is either undervalued or fairly valued. A crash could come at any time, but that’s not the point of this article.

Conclusions

Sounds too complicated? Here’s the simple recap for today:

Beware of the backward-looking nature of this commonly used metrics: they should not be used to anticipate the future (nobody can do that of course);

Beware of potential distortions in the way they are calculated. In particular, the significant influence of the most dominant stocks and

If you have any questions on these metrics, let me know with a direct message or via mail at businessinvestbi@gmail.com.

As usual, thank you so much for your valuable time.

Francesco - Business Invest

I think this is pretty cool. Never been a fan of either for pretty much the reasons you state.

I think to be fully accurate tho, you’d need to make those adjustments to mcap/gdp historically too. And then look at those averages compared to today, so that that 100% figure isn’t really the focal point.